South-east Asia seeks data centre investments – but must reckon with their thirst

With rapid data centre growth straining the region’s water supply, the race is on for alternative water sources and cooling technologies.

[SINGAPORE] Soaring AI demand has brought hefty data centre investments to Johor – yet the Malaysian state’s local government recently narrowed this project pipeline.

In November, it halted approvals for Tier 1 and 2 data centres, which have simpler infrastructure. The reason: water.

Tier 1 and 2 data centres tend to have older and more water-intensive cooling mechanisms. One such facility might use as much as 50 million litres a day, according to a government official quoted in Malaysian news outlet The Star.

Across South-east Asia, many cities seek foreign investment in the form of data centres, but must therefore grapple with the facilities’ insatiable demand for water.

As the chairman of Malaysia’s primary water regulator put it: “We don’t want a situation where data centre operators have water and regular Malaysians don’t have water at home.”

Data centre demand puts a further strain on water-strapped Johor, which already sees supply disruptions such as one that hit over 1,000 households in the 2024 Hari Raya festive period.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

River pollution also disrupts household supply, says Zayana Zaikariah, a senior researcher at Malaysia’s Institute of Strategic and International Studies. In November, almost 800,000 people faced water disruption due to pollution in the Johor River.

“These disruptions raise questions of prioritisation: who gets water first when supply is constrained?” she notes.

“While the disruptions put a question mark over the reliability of water supply for data centre operations and investment flight risk, the bigger worry is on the growing competition between industrial demand and surrounding communities in data centre hubs.”

Investment at what cost?

Policymakers face a dilemma as data centres represent significant foreign direct investment, from both pure-play data centre operators and tech giants such as Microsoft and Google.

As a side benefit, data centres drive demand for local renewable energy projects. These centres may sign power purchase agreements for as long as 20 years; such long-term offtake helps solar and wind projects attract the financing needed to get off the ground.

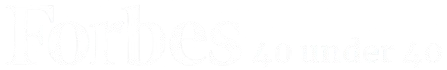

South-east Asia is poised for strong data centre expansion as both US and Chinese players ramp up capacity, says Charles Yonts, head of Asian sustainability research at Macquarie Capital.

He names Johor as the biggest growth market, but adds: “(The market in) Thailand, near Bangkok, is growing faster from a smaller base. And activity is picking up all over – Batam, the Philippines and Vietnam are particularly interesting.”

But while data centres are notorious for high energy needs, their water usage is the “hidden footprint of the digital economy”, says Professor Lee Poh Seng of the National University of Singapore (NUS).

“Historically, many stakeholders optimised for (energy) and treated water as secondary,” he notes. “The AI wave forces a re-think because the same design choices that historically improved energy performance can increase water exposure in the tropics.”

Many data centres in South-east Asia use chilled-water systems paired with evaporative cooling towers. These are more energy-efficient than air cooling, but use more water due to loss from evaporation.

Says Prof Lee: “South-east Asia can continue to grow data centres at pace only if it rapidly pivots to water-lean cooling… and reduces reliance on treated potable supplies.”

Lower-tier facilities are not the only problem. “Hyperscale” data centres that handle massive workloads are typically Tier 3 or higher, and more water-efficient – but still need huge volumes.

A 100-megawatt hyperscale data centre in the US consumes 2 million litres of water a day, estimates the International Energy Agency (IEA). That’s equivalent to the daily needs of some 6,500 households.

“Hyperscale data centres can withdraw as much water per day as a medium-sized town,” says Trung Ghi, head of the energy and utilities practice at consultancy Arthur D Little in Asia Pacific.

Deals flow in

With policymakers now demanding water sustainability, data centre companies are investing in alternative sources such as recycled water.

Hyperscale player Bridge Data Centres (BDC) tries to “decouple data centre operations from community water supply as much as possible”, says its chief executive Eric Fan.

The company has eight hyperscale data centre campuses, with five in Malaysia and the rest in Thailand and India.

“Rather than relying on potable water, we design campuses around alternative and reclaimed water sources and plan water infrastructure at a campus scale, not building by building,” he says.

For instance, BDC is developing a water reclamation plant to treat municipal effluent for data centre cooling in Ulu Tiram, Johor.

This benefits not just the local community, but BDC’s bottom line. Reclaimed water can cut cooling-related water costs by 30 to 50 per cent compared to potable supply, estimates Fan.

Another hyperscale player, AirTrunk, is developing one of Malaysia’s largest recycled water supply schemes with Johor Special Water, a unit of a state company. AirTrunk has two data centres in Johor, as well as two in Singapore.

As data centre operators strive for water efficiency, third-party water companies see opportunities.

Boston-based Gradiant is planning to develop domestic wastewater recycling plants for data centre clients to tap for cooling, in locations such as Johor and Selangor.

Having supplied water solutions for industries such as semiconductors and energy, the company recently expanded into the data centre segment in the US and Europe.

It is in early talks with the Singapore government to provide water treatment solutions for the upcoming data centre park on Jurong Island.

With water demand from hyperscale data centres nearing that of the semiconductor industry, the “biggest roadblock” for operators is securing approvals for water consumption, says president Govind Alagappan.

“Increasingly, we are seeing a trend of both governments and utilities requiring data centres to look for alternative sources of water,” he says. “They don’t want data centres to be drawing down from potable water supply.”

“So the natural driver in many parts of the world has been to look for recycling of domestic wastewater.”

In Singapore, players such as AirTrunk, Keppel and Singtel-owned Nxera use NEWater. The high-grade non-potable reclaimed water is meant for industrial purposes – but also added to reservoirs, contributing to potable supply.

Using NEWater is more sustainable than tapping potable water, but it is still a “premium resource with embedded energy and carbon”, notes Prof Lee.

“(If) it is used mainly for evaporative cooling towers, much of it is effectively consumed and not recovered. The long-term sustainable direction for tropical data centres is not just switching to NEWater but reducing reliance on evaporation altogether.”

Race to cool

In the long term, data centres must use less water for cooling – which requires new technologies.

These include direct-to-chip liquid cooling, where cold plates on chips remove heat and send it into a controlled liquid loop.

AirTrunk uses this for high-density racks, paired with a form of evaporative cooling that is more water-efficient. At one of its Johor facilities, liquid cooling has delivered up to 23 per cent in energy savings.

Nxera’s upcoming data centre in Tuas – its third in Singapore – may have the largest deployment of direct-to-chip liquid cooling in the country, says chief executive Bill Chang.

“These advanced cooling technologies can reduce both water and energy intensity compared with more traditional cooling approaches,” he says.

Immersion cooling, where servers are submerged in fluid, offers “the most dramatic” reduction in water usage as it eliminates the need for air conditioning and cooling towers, says Trung of Arthur D Little.

But he notes: “The main barriers in South-east Asia today are high upfront costs, operational unfamiliarity, and a still-maturing ecosystem for maintenance, warranties, and skills.”

Another emerging idea is locating data centres near or atop water bodies. Keppel, for instance, plans to build a floating data centre in Singapore that uses seawater for cooling.

It “features a modular design, which can be scaled up quickly upon customers’ demand”, says the company’s chief executive for data centres, Wong Wai Meng.

The company previously told BT that modules could be shipped to cities near water bodies, such as Hong Kong, Shanghai or New York.

But Prof Lee notes that floating solutions face technical challenges such as corrosion and the build-up of barnacles or algae, which can degrade cooling performance over time.

He believes that more players will take hybrid approaches: data centres that are located on land but tap nearby seawater for cooling.

Water for power

Nor is direct water use the only concern.

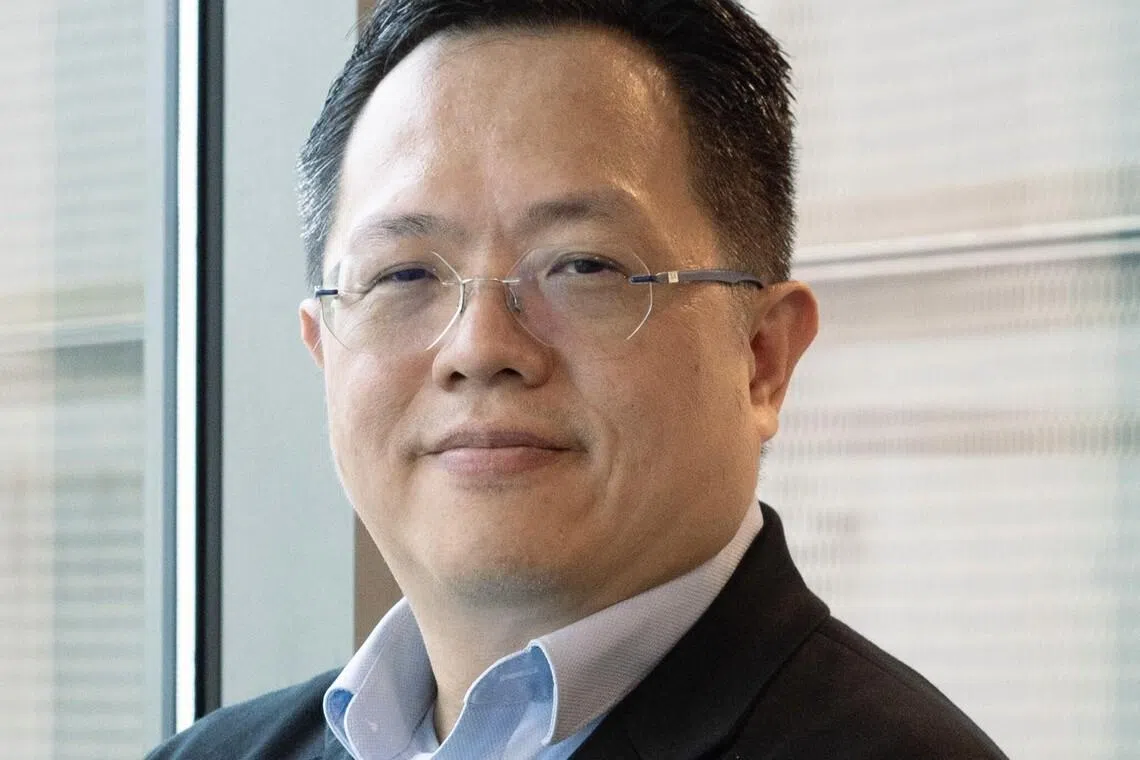

One “point that tends to get lost”, says Yonts of Macquarie, is that data centres’ indirect water consumption for energy – as water is used to cool power plants – is far greater than their water consumption for cooling.

Globally, data centres use about 560 billion litres of water annually, according to a 2025 report by the IEA. But only about a quarter of this is for cooling. A hefty two-thirds is used in electricity generation or by the primary energy supply, with the rest for chip manufacturing.

“So the biggest lever to reduce water consumption by data centres is actually shifting power supply to renewables,” concludes Yonts.

The global energy transition is thus key. Unlike power plants that burn fuel and require cooling, solar and wind power require little to no water for cooling.

Prof Lee believes that South-east Asian policymakers and data centre operators will have to recognise that water and energy planning cannot be separated.

Regional solutions

The race for solutions is set to accelerate as data centres’ water footprints come under greater scrutiny from policymakers as well as sustainability-focused investors and lenders.

Malaysian environmental groups have also begun to draw attention to this, says Malaysia-based researcher Zayana – though efforts have been “moderate” compared to issues such as rare earth mining, with no protests so far.

“It could be likely because many of the new facilities are still under construction or early in operation,” she adds.

Still, data centre operators should be more transparent “so that policymakers and the public can clearly assess operational accountability and real economic value”, she argues.

Current policies and guidelines for data centres are largely reactive and rely on voluntary benchmarks, she adds.

“With more property developers entering the sector – some without deep data centre operating experience – it raises questions about compliance under a voluntary regime.”

Prof Lee suggests that regulators could make water sustainability a condition for approving data centres. This would be similar to existing conditions imposed on power connections, land use and environmental performance.

He also expects city planners to more closely integrate reclaimed water systems, industrial water loops and coastal “heat sinks” – bodies of water that can absorb and carry away heat.

South-east Asia could become a “proving ground” for data centres that operate sustainably in tropical conditions, he says. “If a cooling strategy works reliably in Singapore or Johor’s high humidity and heat, it is deployable globally.”

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.