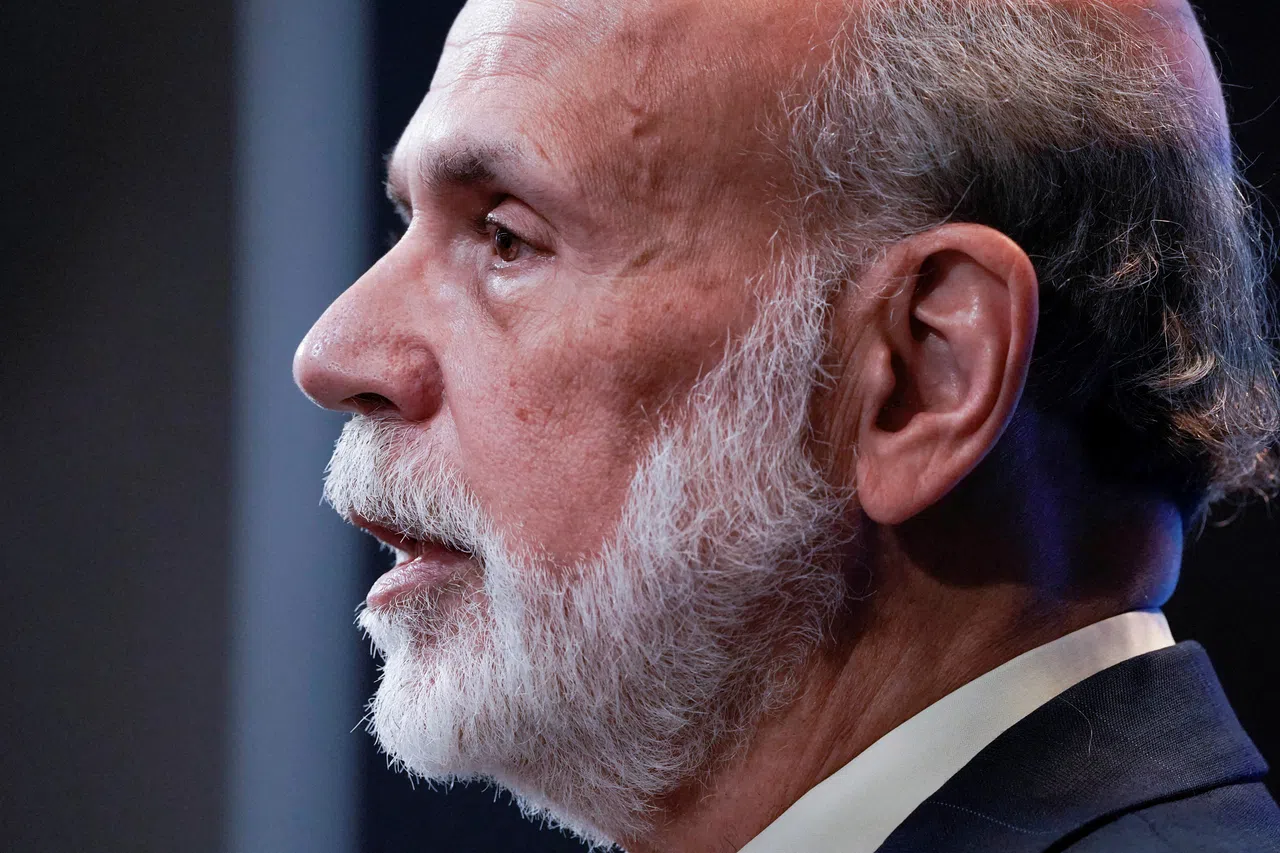

Former Fed chief Bernanke to set out Bank of England reforms

FORMER Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke will set out on Friday how the Bank of England should reform its economic forecasting, after a surge in inflation to its highest levels in more than 40 years turned a spotlight on the central bank’s inner workings.

The eight-month review, commissioned by the BoE’s court of directors and due out at 1100 GMT, is likely to recommend scrapping some of the ways that the British central bank has communicated its thinking since it gained operational independence in 1997.

However, it is unlikely to prompt any immediate shift in the BoE’s assessment of the economy.

“Ultimately, we don’t expect the Bernanke review to be a game changer for markets, or impact the direction of near-term policy,” Sanjay Raja, an economist at Deutsche Bank, said in a note to clients last week.

Investors expect two quarter-percentage-point rate cuts by the BoE this year, starting in August or September. The central bank forecasts inflation will fall below its 2 per cent target in the coming months – down from a peak of 11.1 per cent 18 months ago – before rising later this year, alongside weak growth.

BoE Governor Andrew Bailey told the Financial Times last month that he expected the central bank’s long-standing ‘fan chart’, which shows a range of possible future paths for inflation and growth based on a single set of assumptions, would “get retired”.

GET BT IN YOUR INBOX DAILY

Start and end each day with the latest news stories and analyses delivered straight to your inbox.

Instead, the BoE may publish more forecasts for inflation and growth based on topical scenarios – for example, if shipping costs jumped or wage growth did not slow as expected.

‘Dot plot’ unlikely

A bigger question is whether Bernanke, who was head of the Fed from 2006 to 2014, will recommend that the BoE move closer to the US central bank’s ‘dot plot’ where each rate-setter anonymously publishes their own forecasts for interest rates, growth and inflation.

The BoE, unlike the Fed and the Swedish and Norwegian central banks, does not publish its own interest rate forecasts.

Instead, it produces two sets of projections for inflation, growth and unemployment. One is based on interest rates staying unchanged, and the other on what financial markets think will happen to borrowing costs over the next three years – similar to the approach taken by the European Central Bank.

Investors often look at the BoE’s forecast for inflation two years ahead to get a sense of whether the central bank thinks the market path for interest rates is too high or low.

The BoE’s current approach divides policymakers. Some former officials have criticised it for locking the central bank into making forecasts which are based on interest rate assumptions the policymakers themselves do not believe.

Others worry that more transparent forecasts for interest rates would be misinterpreted by the public as a commitment rather than a best guess which was likely to change.

Goldman Sachs economists James Moberly and Sven Jari Stehn said it was more likely that Bernanke would heed these concerns and recommend a greater use of scenarios.

In 2013, the BoE rejected proposals from an external review that recommended members of its Monetary Policy Committee publish individual growth and inflation forecasts, similar to dot plots.

Bernanke is also likely to look more into the nuts and bolts of the BoE’s forecasting processes – which a parliament committee last year heard relied on “inadequate” models that were unsuited to dealing with very high inflation.

Catherine Mann, a current BoE policymaker, has criticised how some models effectively rule out the possibility that inflation can get stuck at a persistently high level. REUTERS